Techniques for moving in the mountains, on individual sections of the route depends on the nature and characteristics mountainous terrain.

Wooded and grassy slopes are crossed along shepherd and animal paths, usually running along warm southern and western slopes, places with sparse vegetation and a thick layer of soil. On paths or flat surfaces they move at an even pace, slowing down at the beginning and end of each transition. The feet are almost parallel, the foot is placed on the heel with “rolling” to the toe at the beginning of the next step. The center of gravity of the body with a backpack should shift vertically as little as possible - small hills and holes should be avoided, stones and tree trunks should be stepped over. An alpenstock or ice ax is carried in the hand in a stowed position; in areas where loss of balance is possible - in two hands in the self-belay position or as additional support.

When moving along grassy slopes, you should use protruding, firmly lying stones, hummocks and other uneven terrain for support; on steep slopes, avoid areas of thick grass and small bushes, and beware of rockfalls over rocky areas. For steep slopes, shoes with corrugated “vibram” soles are required; in case of slippery, for example, wet or heavily snowed surfaces, as a rule, “crampons” and rope belay are used. To gain height, tourists either move in short, steep zigzags or make long, gentle traverses around rocky areas. When lifting head-on, the legs are placed with the entire sole, the feet (depending on the steepness) are parallel, half-herringbone or herringbone; when ascending obliquely or serpentine - on the entire foot in a half-herringbone pattern (the upper leg is horizontal, loading more on the outer welt of the shoe, the lower leg is slightly turned with the toe down the slope, with a greater load on the inner welt). When descending straight down a not very steep slope, the feet are placed parallel to the entire sole or with a predominant load on the heel, and they move with their backs to the slope in quick, short, springy steps, with their knees slightly bent (but not running). They go down a steep slope sideways, obliquely or serpentine, with their feet placed in a half-herringbone pattern, as when ascending. An ice ax or alpen pole on steep slopes when ascending and descending is held with both hands in a position ready for self-arrest; in case of a fall, it is used as a second support point if necessary. IN dangerous places organize belaying with a rope through tree trunks, rocky ledges, as well as over the shoulder or lower back.

Scree slopes are climbed in groups with minimal intervals between participants. When moving along them, you must remember that steep scree areas are especially dangerous due to rockfalls. They climb up the shallow scree “head-on” or in a serpentine way, placing their feet parallel, compacting the step with gradual pressure until the sliding of the scree stops. You should lean on your entire foot, keeping your body vertical (as far as your backpack allows). An ice ax (alpenstock) is used if necessary, leaning on it from the front side. They descend in small steps, placing their feet parallel with an emphasis on the heel, if possible, sliding down a mass of small stones and not allowing their feet to sink deeper than the top of the boot; ice ax in position ready for self-arrest. They move along cemented or frozen scree in the same way as along grassy slopes.

Along the middle scree, it is recommended to move obliquely or in a steep serpentine, and at the turning points, the guide should gather the entire group so that tourists, for safety reasons, are not on top of each other. Unstable steep, so-called living screes are especially dangerous. Sudden movements should be avoided; legs should be placed on the entire foot carefully, gently, choosing parts of the stones facing the slope for support. The ice ax is held in the hand without resting it on the slope.

On large scree they can easily move in any direction. The movement is carried out by stepping from one stone to another, changing the pace in order to maximize the use of the inertia of the body with a backpack and avoiding large jumps. When descending and ascending, you need to place your feet on the edges of the stones, closer to the slope. Stones and slabs that have a significant slope should not be used.

Tourists pass through rocky slopes, ridges, couloirs and ridges with a preliminary assessment of the difficulty and safety of individual areas. The main indicators of the difficult terrain of a rocky terrain are its average steepness and its constancy throughout the entire section. When assessing the steepness, take into account that from below the slope it appears shorter and flatter, especially its upper part. The view from above and “head-on” seems to increase the steepness, and the presence of steep drops conceals the distance (the height and steepness of the slope helps to determine the dropping of small stones). The correct idea of the steepness of a slope or edge is given by observing it from the side (in profile) or directly accessing it. The safest places for movement are ribs and buttresses; the simplest but most dangerous are the couloirs due to possible rockfalls. It is allowed to use the lower part of the wide couloirs to bypass the steepest lower part of the ribs and buttresses, the upper part of the couloirs when reaching the ridge crest in dry weather in the early morning hours. It is prohibited to move along the couloirs during snowfall, rain, or immediately after precipitation. Walking along the ridges is safe at any time of the day, except in cases of bad weather and strong winds. The “gendarmes” encountered on the ridges walk around the slopes or climb over them.

The basis of movement on rocks is the correct choice of route, the use or creation of supports and the correct position of the center of gravity relative to the support. There are free climbing using natural support points, ledges, cracks and so-called artificial climbing, when support points are created using rock and bolts, bookmarks, ropes, loops, ladders. Free climbing can be external - along the wall and internal - in crevices and fireplaces. According to the difficulty of movement, rocks (rock routes) in tourism are divided into 3 groups:

- Easy, overcome without the help of hands (they use their hands occasionally to maintain balance).

- Medium, requiring a limited arsenal of climbing techniques and periodic belaying.

- Difficult ones, which may require any free and artificial climbing techniques, require continuous belaying of the walker and self-belaying of the belayer.

The arms and legs can be used for gripping, holding and pushing. When grabbing, the hands work. arr. to maintain balance by loading the supports from above, side and below. The main weight falls on the legs. For stops, uneven rocks are used that are located below shoulder level and are unsuitable for gripping. The force is directed mainly from top to bottom and is transmitted through the palm or part of it and the soles of the feet. Spacers are used where there are no protrusions on the rock surface for grips and stops, and the location of the rocks allows this technique to be used.

The following basic rules are followed on rock routes::

- before starting the movement, determine the route, rest areas, insurance and difficult sections;

- The climb is carried out, if possible, in the shortest direction - vertical, choosing the simplest path.

Shifting to the side (transition from one vertical to another), if necessary, is carried out on the flattest and easiest section of the slope. Before loading a rock support, its reliability is checked (inspection, hand pressing, hitting with a rock hammer), after which they try to use it first as a grip or a rest for the hands, and then as a support for the legs. For a stable body position, three points of support are maintained, either two legs and an arm, or two arms and a leg. The main load, as a rule, is borne by the legs, while the arms maintain balance. In order to save forces, friction (stops and spacers) is used as much as possible. They move over rocks and load supports smoothly. In areas where there are good supports for the arms and poor ones for the legs, the body is kept further away from the rock; in areas where there are good supports for the legs, the body is kept closer to the rock. Before a difficult section, you should rest, determine points of support and grips in advance and overcome it without delay so that your arms do not get tired. If it is impossible to continue moving, you need to go down to comfortable spot and look for a new lifting option. The arms get tired less if the holds are located no higher than the head; when pulling up, they help by straightening the legs. For greater stability, keep your arms and legs slightly apart and try not to rest on your knees. The design of modern hiking shoes allows you to use the most minor uneven terrain to create support. To increase the adhesion force of the boot to the rock, the pressure of the foot must be perpendicular to the surface of the support. For small ledge surfaces, the foot is placed on the inner welt of the boot or on the toe.

When climbing rocks, extreme attention, caution, and confidence are required. In case of a fall, you should keep your hands in front of you so as not to hit the rock and, if possible, catch on to it. Descent on simple rocks is performed facing away from the slope, leaning on the palms of your hands, bending your knees and body, but without sitting down. On rocks of moderate difficulty, they descend sideways or facing the slope, with their arms maintaining balance and the body almost vertical. On difficult rocks in short sections they descend facing the slope, but more often they use rope descent: sports, the Dulfer method or using braking devices. Before organizing the descent, you should make sure that the rope reaches the platform from where you can continue moving or organize the next stage of the descent. The main rope for descent is secured to a rocky ledge directly or using a rope loop, as well as to rock hooks with a carabiner or a loop made from a cord. The strength of the protrusion is carefully checked; sharp edges that can damage the rope at the bends are blunted with a hammer. Old hooks and loops must be tested for strength; if there is the slightest doubt, they are replaced with new ones. The loop of the cord should be double or triple. All members of the group, except the last one, descend with the top rope using the second rope. The last participant descends on a double rope with a self-belay. Before the last participant descends from below, they check how the rope slides; if it jams, its fastening is corrected. The second rope, also used for pulling, is passed through the chest carabiner by the last person descending. The descent along the rope is carried out calmly, evenly, as if walking along rocks, avoiding jerks. The body is held vertically, slightly turned sideways towards the slope, legs slightly bent and placed wide on the rock.

Snow and firn fields and slopes, as well as closed glaciers, are crossed, if possible, in the cold season. Particular attention is paid to possible avalanche danger, taking into account the steepness of the slope, the time of the last snowfall, the orientation of the slope, the time and duration of its illumination by the sun, and the condition of the snow. When moving on snow and firn, they follow the principle of maintaining “two points of support” (leg - leg, leg - ice ax or alpenstock). The main efforts are spent on trampling tracks and knocking out steps.

For safety reasons, tourists adhere to the following basic rules:

- on a soft snowy slope, the foot support is pressed gradually, using the property of snow to freeze when compressed, avoiding a strong kick on the snow;

- if the crust is weak, it is pierced with a foot and the support under it is pressed;

- on a steep crusty slope, rest the sole of the boot on the edge of a step cut into the crust, and rest the shin on the crust;

- the body is held vertically, the steps (supports) are loaded smoothly simultaneously with the entire sole;

- the leader's step length corresponds to the step length of the shortest member of the group;

- all members of the group follow the trail, without disturbing, and if necessary, correcting the steps; with a strong crust and on dense firn, the steps are stuffed with a boot welt, cut out with an ice ax, or using “crampons”;

- in the event of a slip, having warned the partner in the rope by shouting “hold”, the one who fell must immediately begin self-restraint, and the belayer must stop the slide at the very initial stage.

They climb straight up along a snowy slope with a steepness of up to 35°. If there is a sufficient depth of soft, loose snow, the feet are placed parallel, compacting the snow with them until a snow cushion is formed. If there is a small layer of soft snow on a firn or ice base, the foot is immersed in the snow with a light blow until the toe touches the hard base. Then, without lifting the toe from the base, press the step with vertical pressure. If the steps slide down under load, double pressing of the steps is used: first, the first portion of snow is pressed with a kick perpendicular to the slope, forming the base for the future step, freezing to the underlying firn or ice, and then, using the snow from the sides of the hole, a step is formed on the resulting base. On a very thin layer of soft snow lying on ice and dense firn, you should use crampons. As the steepness of the slope and the hardness of the snow increase, they switch to zigzag movement at an angle of 45° to the “water flow line,” knocking out steps with the welt of the boot with oblique sliding blows, with the obligatory observance of the rule of “two points of support.” On slopes with firn muddy to a considerable depth or covered with dry snow, as well as on slopes with a steepness of 45° or more, a straight upward climb in three strokes is used. When traversing using the three-beat method, they step over with an additional step. Fresh soft snow, softened by the sun, sticks in a lump on the soles of the boots. It must be immediately knocked down by hitting the edge with an ice ax with almost every step.

The deep frost and frosty, sandy, recrystallized snow that sometimes forms under the crust cannot be pressed. In the first case, only a layer of crust is used for lifting, in the second, they punch a trench to a solid base, organizing insurance at its bottom through an ice hook or ice ax and knocking out the steps.

On a snowy slope of low and medium steepness they descend with their backs to the slope, straight down or slightly obliquely. In the loose and muddy snow they walk almost without bending their knees with short steps. When descending on harder snow, the tracks are made with a blow from the heel (to maintain balance, you should lean on the pin of the ice ax). If the snow slope is avalanche-proof, then you can go down in a line - each participant makes his own tracks; otherwise you need to follow the trail. On a crusty, firn or glaciated snow slope of great steepness one descends, as a rule, facing the slope for three steps, using and maintaining steps laid by the leader, or along a railing fixed to ice axes, an avalanche shovel, an ice hook or a snow anchor. On non-steep snow slopes that can be seen from the bottom, sliding descent (planing) is allowed - on your feet, sitting, on your back or on your feet and a backpack. The slope must end with a safe slope and have no sections open ice, rocky outcrops, large stones and pieces of ice; snow - free from medium and small stones. Planing sitting and on the back is used to overcome narrow cracks and bergschrunds with an overhanging upper edge, with mandatory belaying with a rope. The person descending must retain the ability to reduce speed and stop at any time.

Self-belaying when driving on snowy and firn slopes is similar to self-belaying on grassy slopes. When moving three strokes, self-belaying is carried out with an ice ax driven into the snow. Self-arrest on loose and softened snow is carried out by sticking an ice ax into the slope above the head with a bayonet and cutting through the snow with the shaft; in case of a fall on dense snow, firn, crust or on a thin layer of snow covering the ice - with the beak of the ice ax.

They move along snow ridges and along them with simultaneous or alternating belay. Exiting to the ridge from the under-eaves side is extremely dangerous; it can only be done in exceptional cases with maximum caution by climbing along the “line of falling water” in the cold time of day and cutting a transverse hole through the eaves, with belay by a partner from a sufficiently distant point. Traverse under the eaves is not allowed. Descent from the cornice is carried out by hemming or cutting with a rope an extended section of the cornice with careful belay.

The technique of movement on ice is determined mainly by the steepness of the ice slope, the condition of its surface, as well as the type and properties of the ice. When walking on ice, they usually use “crampons”, less often triconi. On steeper slopes, if necessary, artificial support points are used, namely: cutting out steps and hand grips, driving in or screwing in ice hooks. Movement in “tricone” boots or “vibram” boots is possible on relatively gentle ice slopes, while the technique of movement is the same as when walking on grassy slopes. When walking on crampons, your feet are placed a little wider than when walking normally. The “cat” is placed on the ice with a light blow with all teeth at the same time, with the exception of the front ones. The body should be vertical, its weight should be distributed evenly over all the teeth of the “cat” if possible. With the next step, all the teeth of the “crampon” should come off the ice at the same time. The ice ax is held in the self-belaying position in both hands - with the bayonet facing the slope and the beak of the head down.

On gentle ice slopes (steep up to 25-30°) they rise directly “head-on”. The legs are placed in a herringbone pattern, with the toes turned depending on the steepness of the slope. The ice ax is used as an additional support point.

On steeper slopes (up to 40°), they switch to zigzag movement at an angle of 45° to the “water fall line.” The feet are in a herringbone pattern: the one closest to the slope is horizontal, the far one is turned with the toe down, along the slope. When moving on slopes steeper than 40° without a backpack or with a light backpack, you can climb “head-on” on the four front (toe) teeth of the “crampons”, which are simultaneously driven into the ice with gentle fixed blows. The feet are placed parallel, the heels are lowered, the body is vertical. The ice ax is held in a self-arresting position in both hands in front of you, leaning on the slope with the beak directed perpendicular to the slope, the shaft is lowered down with the bayonet. Movement in three beats, observing “two points of support” (the beak of the ice ax is a leg or two legs). The descent on gentle slopes is carried out straight down in a “goose step”, driving all the teeth of the “crampons” into the ice at the same time. If the slope is steeper, they descend using a rope. When moving with a load on steep sections, they resort to cutting down steps, while climbing up serpentine roads. The step should be spacious enough, without ice hanging over it, with a horizontal or slightly inclined surface towards the slope. On a slope with a steepness of less than 50°, the steps are cut in the so-called open stance with two hands; on steeper slopes, in a closed stance with one hand. To descend, cut out double steps and move at an extra step, leaning on the pin of an ice ax in the lanyard position. The steps are located one below the other at approximately an angle of 15° to the “water fall line”. When moving along an ice ridge, steps are usually cut on its flatter side or the ridge is partially used.

Safety on an ice slope is ensured by self-belaying with an ice axe, a piton belay, a belayer's self-belaying, or using fixed rope railings. The hooks are hammered or screwed into pre-cut steps. The railing rope for ascent and descent is secured to double hooks, an ice post (usually 50-60 cm in diameter) or an eye drilled with an ice drill.

Glaciers pass, whenever possible, along rock-free strips of ice, longitudinal ridges of surface moraines, along randklufts or trenches between coastal moraines and valley slopes, along (or along) the ridges of coastal moraines. Access to the glacier is possible from the lower part of the valley through the end of its tongue or along the end moraine, bypassing the end of the tongue along the ridges of coastal moraines or randklufts, with ascent to the slopes of the valley and traverse them to a part of the glacier convenient for movement. Overcoming icefalls is carried out along a pre-planned route with a preview or reconnaissance of the entire upcoming path: bypassing along the slopes of the valley, coastal moraines or randklufts, directly along the ice along the shores or in the middle (with a tray-shaped surface or thick snow cover). The possibility of a through passage may be evidenced by the median surface moraine, stretching from the upper reaches to the base of the icefall. Of the two parallel branches of the glacier, the longer one is less difficult. Icefalls with a southern and southwestern exposure, with the same steepness or difference in height, are easier to pass than those with a northern or northeastern exposure. Cracks are overcome by going around (tacking), jumping, including without backpacks, followed by transferring them by hand, or using a descent to the bottom and ascent to the opposite side, and sometimes with an air crossing similar to crossing rivers. The Bergschrunds are crossed on snow bridges. If they are absent on the climb, the upper edge (wall) is overcome with the help of ice axes stuck into it or an “oblique hole” is made - a manhole. Descent - by jumping or on a rope (“sitting” or “sports way”). On closed glaciers, which pose a particular danger, you should move in groups of 2-4 people. with an interval between participants of at least 10-12 m, bypassing the zones of cracks that arise on the convex parts of the glacier and outer. the edges of its turns. When crossing unreliable snow bridges over cracks, alternate belay or belay with the help of railings is necessary.

A closed glacier or a trap for the careless

Vasilyev Leonid Borisovich – Kharkov, doctor, MS USSR.

Photos by the editor – doctor, MS USSR

Rely on a friend...

In the mountains there are situations from which no one is immune. The most experienced fall into avalanches and ice collapses, the most careful do not avoid breakdowns. Spontaneous rockfall can be unpredictable. But the cracks on the closed glacier are notscary if you constantly remember them and adhere to the old rule– in the area of possible cracks, move only in conjunction and only with certain precautions. The latter is extremely important – the mere attachment towearing a rope does not guarantee you from harm.

I I heard about professional guides who, having climbed a difficult wall in the Alps without insurance, contact before returning along the glacier. If the local mine rescuers the body of a person is removed from a crack, not properly equipped, without all the devices provided for by the situation, not a single insurance company will pay his family was entitled to money under the contract.

In fact, you definitely need to visit a glacial crevice to avoid any problems. desire to fly there someday, but the best way to do this is during training sessions retrieving a stuck one. I'll share another experience...

Crack

Andrey Rozhkov's team, participating in the Moscow Winter Championship, descended from Ullu-tau. I ran ahead of the others along our climbing tracks on a flat 20 degree slope. At some point, my leg fell softly into the void, and I slowly sank into the snow up to his waist, held on the surface by a bulky backpack. My legs didn’t feel any support, but I, not yet “getting the hang of” the situation, began to flounder, trying to get out of the hole. What happened next is still etched in my memory like a slow motion movie. The edges of the crust holding me sank, and I plunged headlong into the snow, hanging on the backpack straps. The next second, the backpack followed me, and I fell into a dark void. A slight lean on the cat against something and I was turned upside down. I fell flat, hitting some ledges. These seconds were endless - I remember that I was gripped not by fear, but by amazement - how long can you fall? It's time to be the center Earth! Finally, I fell backwards onto the ice plug. The backpack failed in continuation cracks, trying to drag me there too. Somehow I pressed my elbows into the edges of the crack, stopping my slide down. Releasing one shoulder from the strap, he turned over onto his stomach. The backpack hung with the second strap on the bend of the elbow. I knelt down and pulled him out black emptiness and looked around. It wasn't that dark in the crack. Smooth went up shiny walls. The snow cover above allowed daylight to pass through. Garlands of icicles lined the top edges of my trap. Overall, it was beautiful. In a tiny The face of Sasha Sushko appeared through the hole, covering the sky. "How are you there?"- he asked, lowering the end of the rope. I untied the ice-fi strapped to my backpack, fastened myself to the rope, and climbed out of the crack myself. The hole in the snow was barely big enough for my helmeted head to fit through – it’s not clear how I slipped through it with my backpack. From the marks on the rope we measured the depth of my hole – 12 meters. Overall, I got off easy – a trap for the carelessit could be much more insidious...

How to behave on a closed glacier without tempting fate? First of all, you must be properly equipped. In the “system”, in a helmet, in crampons. (Cats It is advisable to wear them even when walking in them is tiring due to the sticky snow.But if you find yourself in a crack – and cats can become the main tool in your self-rescue. Without them, you will not be freed from possible jamming in a narrowing crack. A helmet will also not be superfluous, considering that in the crack the backpack is almost will probably turn you upside down). Zhumar, 2-3 ice screws, the same number of carbines or quickdraws should hang on the belt, in the pocket of the anorak - there is a grasping and minimum 3 meter end of the cord.

The best outcome for someone who has fallen into a crack withwith such equipment - hanging on a rope. Using a jumar and tying a Bachman knot,you can climb it yourself evencase when your partner is not capable of anything. If only he could secure rope! Ideally, your partner, having secured the rope coming towards you on an ice ax or “storm”, and having secured it with a grabber, will crawl to the edge, throw you the second end of the rope, having first carefully cleared the edge of the crack, placing an ice ax, jacket, or backpack under the rope (all insure!).

If you fall into a crevasse without a rope or with a rope in your backpack, the situation becomes more complicated. Already When you “land”, options are possible. At best, the crack is shallow, withflat bottom, or you will be lucky like me and you will find yourself in a traffic jam. It's much worse if you will get stuck in the narrowing of the walls or you will fall into the water. There are holes, right through to the rock bed, piercing the body of a snowfield or glacier. Looking down you can see the stream rushing under the ice arches. This is the worst option!

Fell into a crack

Not better and jamming, which can cause serious injury. Moreover, in a narrow crackyou may be covered with a layer of snow and ice, part of the snow falling behind you ceilings Either way, you'll be soaking wet in a couple of minutes. (Alarming in There is only one thing in this situation - after 15-20 minutes the failed person stops responding to calls from above...). Therefore, in any case, you must go down to the victim who has reached the bottom as quickly as possible, taking with you a first aid kit, warm clothes, a stove and the necessary technical equipment. But if you are able to act in this situation, fight for life. Throw off the snow and push it deeper into the crack, until he froze to death. Having twisted the ice screw as high as possible and threaded a rope into its carabiner or a cord tied to your belt, tie a loop at the other end and try insert your foot into it. Pulling yourself up on a hook and loading a simple chain hoist with your foot, likeget rid of the jam as quickly as possible. If you succeed, it’s a victory. Samemethod, alternately twisting the drills higher and higher, begin to climb the wall. To release the cord, you will have to hang from the lanyard each time. Things will work out faster if you have a couple of cords. It’s better to get rid of the backpack, leave it it by tying it to a hook or to the end of a rope. The hardest thing is to get over the edge cracks if the rope cuts deep into it. In this case, there should be a lead the zhumar, and the grasping or Bachmann knot is behind it. A double rope and help from above will make the task easier. Remember - there are no hopeless situations for the prepared person!

As a rule, novice climbers consider themselves safe, already only tied to a rope. It is the illusion of insurance if your partner is walking closely behind you and holding the rings in their hands. Snow does not create friction, and it is naive to think that this is how you can resist the tug of a wet rope. It’s good if your partner doesn’t fall into a crack following you. Make him walk the entire rope. By the way, for a deuce it shouldshorten to 12-15 meters, even better to go on a double rope. It is advisable to tie onrope in front of you with a guide knot and insert an ice ax into it - then, having fallen during a jerk, It’s easier to hold the rope and, after twisting the “drill,” click the finished knot into it. And yet, on a single rope you should move with a team of more than two people. (Attention! Avoid walking in the middle of the bunch on the “sliding”! It cost my friend his life,but more on that below...).

Hermann Huber in his book “Mountaineering Today” (note that this is“today” was 30 ago) offers a rational way of linking two toglacier: the rope is divided into three parts, and to the middle one (it is slightly shorter than the two end ones)partners become attached. The loose ends wound on each are intended tothrowing to someone who has fallen into a crack. Everyone can tie a grasping knot on a rope a meter from their chest.

Other guides recommend preparing the leg “stirrup” from the cord, and tie it with its second end, passed under the chest harness grasping on the main rope at chest level. But even having prepared in this way, it is better to avoid falling into a crack.

Careful observation of the glacier surface will tell you the nature and direction of the cracks - it is unacceptable for both to end up above a crack parallel to the movement of the ligament. Sometimes, especially in oblique morning or evening light, closed cracks are guessed by the change in color of the snow that has slightly subsided above them. In suspicious places, probe the path with every step. A ski pole will provide you with an invaluable service. Without a ring, an ice ax is less effective for this purpose. Remember also that falling through first is more dangerous on the descent - in this case there is a high chance of your partner falling into a crack. Heavier or careless, coming second on the climb, failing, too risks pulling your partner along with you (see below!). Therefore, on the descent and ascent you should not shorten the rope to the same extent as on a flat glacier.

But in any case, a person who anticipates danger or is at least prepared for it is capable ofresist her. Here is an unenviable situation from which my friend Anatoly Lebedev, now the director of the company “Ryukzachok”, came out with honor: 1982, the pair A. Samoded - A. Lebedev worked on an extreme route - a 400-meter sinter “icicle” on the wall of Moskovskaya Pravda (Y -3 Pamir). In the heat of the moment, they made an unforgivable mistake - they hung all the ropes and returned to the tent untied. Already in front of the tent, Tolya fell into a closed crack - an ice “glass” filled with water. It didn’t reach the bottom; the smooth walls went up 6 meters. In this stalemate Anatoly did not give in to panic - floundering in the icy water and plunging headlong every time he tried to do something, he was able to pull out an ice ax from behind his backpack, remove an ice hammer from his belt, and (fortunately, he had crampons on his feet!) he began to climb out of the traps. It is difficult to calculate how fast Alik Samoded ran under the wall to get the rope, but by the end of the record climb he managed to throw the end of it to his partner. Of course, this feat would have been easier to avoid. But how different is its outcome from finals sad stories which are given below...

1. 08/03/1961. V. Wilpata, 5a.

A group of instructors from the Torpedo a/l, returning after the ascent, passed the last section of the icefall before the Volginskaya overnight stay. When crossing a crack, a snow bridge under the group leader N. Pesikov collapsed, and it fell to a depth 20 m, receiving extensive injuries. There was no insurance.

2. 27.07.1968. Peak of Communism.

The group organized a bivouac on the plateau of Communism Peak (6200 m). The tent was set up in a safe place, about 10 m from a narrow crack. At about 18.30 E. Karchevsky left the tent where the other participants were. A few minutes later they called to him, but he did not respond. As the footprints in the snow showed, Karchevsky fell into a crack. A rope was lowered into a hole in the snow (ondepth of 30 m), which they began to pull from below. But repeated attempts they were unsuccessful in approaching the victim. The crack at the top was as wide as 45 cm, and then narrowed to 20 cm. Falling 30 m, Karchevsky’s body jammed and froze in ice.

3. 01.08.1973 . Peak of Communism, Belyaev Glacier.

The Kursk expedition aimed to climb the peaks of Communism and Pravda. To monitor the groups and maintain radio communications, 4 second-class climbers were brought in under the general leadership of P. Krylov. 08/01/73 at 6 o’clock two groups of climbers left camp “4700” up to an altitude of 5000 m, they were accompanied by observers G. Kotov and N. Bobrova. Everyone walked up to an altitude of 5000 m without communicating. From here the observers returned to camp “4700”, where they received a request to go up again and bring up forgotten cats. Kotov and Krylov brought their crampons to 5200 m. On the descent they walked without contacting. Kotov, who walked first, carried the rope on his backpack. Suddenly he failed. He did not respond to Krylov’s screams. Only the next day the body of G. Kotov was discovered at a depth of 35 m under a one and a half meter layer of snow and ice debris.

4. 28.07.1974 . Peak of Communism – plateau of the peak of “Pravda”.

Two bundles of the expedition of the Ukrainian Council of the DSO "Spartak" to remove the body of A. Kustovsky from the South the walls of Communism Peak worked on the plateau of Pravda Peak. The first in the group of five was B. Komarov. He walked quickly, without testing his way with an ice ax. The second in the bunch, Morchak, carried rings of rope (2-3 meters). The distance between them was about 8 meters. Suddenly, Komarov fell into a crack, but was detained by Morchak. Komarov hung at 3-3.5 meters from the surface. The crack was deep, with smooth edges, less thanmeters. When asked if he could help with pulling, he answered in the affirmative. Firstan attempt to pull Komarov out ended unsuccessfully - the rope crashed into the firn edge. Komarov began trying to throw his leg over the edge of the crack. Komarov did not respond to the demand to stop these attempts and, as a result, turned upside down, after which stopped answering questions. After treatment, the edges of Komarov’s crack were removed withoutsigns of life. According to the group, it took 8-12 to extract Komarov from the crack. minutes. The attempt at resuscitation lasted 2.5-3 hours, but to no avail. The cause of Komarov's death was intracranial hemorrhage as a result of a head injury.

5. 04.11.1975. V. Kazbek.

The Alpiniad of the Kharkov Regional Council of DSO "Zenith" was held with numerousorganizational violations. On November 3, the participants climbed to the weather station.When returning from the exit, the group walked tied with one rope. Degtyarev was the first, followed by Demanov, in the middle, Taran and Dorofeeva were on sliding carbines. After some time, Degtyarev fell into a crack up to his chest, from which he chose himself. Taran's reaction was slow - he began to belay Degtyarev only after shouting: “What are you standing for? Pull the rope! Group moved further and in the same place where Degtyarev was, Taran falls into a crack.Demanov managed to secure one end of the rope to the ice ax only after 15 minutes(the snow lay on the ice in a thin layer). The battering ram hung on a rope and a cord onat a depth of 3-4 m on the chest harness with the head thrown back. The face was covered with snow. Since Taran was hanging on the sliding one, it was impossible to pull him out by the free end of the rope.managed. They also couldn’t secure the other end, so they lowered Taran to the bottom of the crack and went for help. However, neither Demanov nor Degtyarev, who is inin an insane state, they could not explain where the victim was. Towards the crack They arrived only at 23:00, but they couldn’t lift Taran (the participant carrying the ice hooks never came up). The body of I. Taran was removed from the crack only on November 5.

6. 10. 07 76 . Peak of the World, Za.

The group of arresters of the 5th stage of the Bezengi a/l left the bivouac on the lat at 5 o’clock. Ullouauz on ascent. We moved along a closed glacier, unrelated. At 6 o'clock running thirdT. Zaeva, while crossing the Bergschrund, fell 15-18 m. Zverev descended to her, placed warm clothes under Zaeva and began to wait for help to raise her, but Zaeva died without regaining consciousness.

7. 06.08. 76. V. Zaromag, 2b.

Two squads of badgeists under the leadership of instructors L. Batygina and Yu.Girshovich climbed V. Zaromag. On the descent, bundles of squads walkedinterspersed. The instructors walked untied. About 13 o'clock in a closed crackParticipant V. Feldman, who was walking in the first group, fell through, next to him was G. Khmyrova from the second group, who came up to the screams, and then came the untied instructor Yu. Girshovich (he lingered on the ice ledge 4 meters from the surface). Girshovich voiced contact with Khmyrova and Feldman, who turned out to bea little to the side. Khmyrova’s leg jammed and she asked for an ice ax. Khmyrova was unable to use the two additional ropes lowered into the crack. Then Girshovich attached himself to them and was lifted up by the participants. Frozen and demoralized, he subsequently did not take any part in rescue operations. Feldman was raised behind Girshovich, but Khmyrov could not be raised. Participant S. Lyubkin, using crampons, reached Khmyrova, who was covered with 30-40 cm of snow. Having freed her jammed leg and pushing her from below, he helped raise Khmyrova (at approximately 14:55). She showed no signs of life. Rubbing and artificial respiration did not help and at 18 o’clock the participants began transporting the body Khmyrovoy down.

8. 12.08.1976 . V. Gumachi, 1b.

Four squads of icons from the Elbrus a/l climbed the mountain. Gumachi andWe began our descent along the ascent path. Instructor Kalganenko, having transferred the leadership of his department to another instructor, put on the skis and began to descend on them in parallel paths for descending compartments. At 11:30 Kalganenko fell into a transverse crack. The skis got stuck across the crack, the fastenings came loose, and Kalganenko fell down 30 m. In 35 minutes. she was removed from the crack, but without regaining consciousness, L. Kalganenko passed away.

9. 03.07.1982 . Levinskaya glacier.

A group of dischargers under the leadership of 2nd category instructor E. Tarabrin left the Alai camp for snow and ice training on the Levinskaya glacier. TOplace The bivouac arrived at 12 o'clock. Before going to class, participant V. Peasants receivedthe instructor ordered to go to the bivouac of climbers from Ivano-Frankivsk, located 500 meters away, to receive advice on the route of the training ascent. Then he had to catch up with the group on the trail running along the end morena to the place of classes. When Krestyannikov didn’t come by 4 p.m.the group stopped training and returned to the bivouac to organize searches. Just on the next day, Krestyannikov’s body was discovered at a depth of 15-17 m in a closed crack 2 kilometers away from the training site.

10. 25.07.1984 . Caucasus, Kashka-Tash glacier .

The training group of the Odessa OS "Avangard" climbed 5b k/tr. on v. Ullu-Kara and went down the Za to the plateau. The team of I. Orobey (MSMK) and V. Rosenberg (1st time) was moving ahead. They approached the open crack without communicating. Rosenberg offered to organize belay, removed the rope and stuck an ice ax in the snow. At that time, Orobey decided to step over the crack using a ski pole, but slipped and fell into the crack. An hour later the victim was raised. Attempts to revive him were unsuccessful.

11. 28.07.88 . Free Spain .

The sports group V. Masaltsev and A. Pisarchik (both CMS) started at three o’clock in the morningclimbing not along route 5b to the peak of Free Spain (B Wall), which was released, but along Za. Motive changing the route (rock hazard) is untenable - this season there is a wallhas been passed several times. About 6 o'clock Masaltsev I crossed a snow bridge and came out onto a snowy slope with a steepness of 20-25 degrees. Pisarchik, who was following him, fell into a crack and pulled Masaltsev into it. Pisarchik jammed at a depth of 25 m, and Masaltsev at a distance of about 7 m in side and somewhat deeper. At first the fallen talked, but after 15-20 Masaltsev stopped answering for a few minutes. Pisarchikwas able to free himself from the jam and,without making an attempt to get to Masaltsev and help, unfastened from the rope, connecting them, took out a second rope and 3 ice screws from his backpack, with the help of whichcrawled out of the crack. At 15:50 the rescue team reached the victim, butfinding signs of life in him. Clerk for violating the rules - with unauthorized change of route, for leaving a comrade in distress, is completely deprived of the title of instructor and sports ranks.

12. 02.02.1990 .Tien Shan, Marble Wall glacier .

A group of observers watching the ascent to the mountain. The marble wall overlooked the glacier. Atmoving along an open (!) glacier in a team, S. Pryanikov, who was second, fellcrack. The width of the crack did not exceed 1 m, but at a depth of 4-5 m it narrowed to 30 cm and then expanded again. Pryanikov’s legs passed through a narrow gap, and his torso jammed, severely squeezing his chest. My partner didn't feel it jerk, because there was a supply of rope. The three of them pulled out Pryanikov without any signs life, resuscitation was carried out for two hours, but to no avail.

13. 24.02.1998 .Caucasus, Kashka-Tash glacier .

Three climbers, having made a winter ascent to V. Free Spain (5b), returned to the tent on the plateau. They followed their many-trodden footsteps, not related. Oleg Bershov, walking ahead, heard a quiet “hooting” behind him. turned around, but did not see his comrades following him. Returning back, I discovered a hole in the snow about a meter and a half in diameter. The ropes remained in the backpacks of those who followed. Only the next day rescuers discovered the bodies of Sergei Ovchinnikov and Sergei Frost in a crack under a meter layer of snow...

I knew the sociable Seryoga Pryanikov, my fellow doctor, I knewKharkov residents Igor Taran and Sergei Moroz, with Igor Orobey a methodological training took place at1st category. It's hard to get rid of the thought that if only they remember the insidious trapped on a closed glacier, everything could have turned out differently... I invite the reader to figure out for himself the mistakes that should be learned from, and try to find the optimal solution, both in the described real situations and in situational tasks compiled by the author.

1. When moving along a glacier in a group of three, the two in front come out onto a closed crack and fall through. The first gets stuck in the narrowing of the crackat 10 m, does not answer questions. The second one hangs in the middle. The third fell on the snow andholds a rope on an ice axe. What are the options for each?

2. When the duo was moving along a closed glacier, the first one went around an open crack,the second moves along it. At this moment the first one falls into the closed crack and with a jerk of the rope throws the second one into the open. Both hang on your rope without reaching the bottom. What are your actions in this situation?

3. In a team of three moving on a rope shortened to 15 m - fortythe middle one, walking on the sliding one, falls into a crack. The partners, torn off by a jerk of the rope, lie in the snow, holding it. What equipment would you like to have in place of each of the three, and what are your actions?

4. Extreme situation: you need to move along a closed glacier in alone. What equipment, what techniques do you use, what will you do, to prevent falling into a crack?

What do we know about glacial crevasses? Only that glacial(ice)crack- This is a glacier rupture formed as a result of its movement. Cracks most often have vertical walls. The depth and length of the cracks depends on the physical parameters of the glacier itself. There are cracks up to 70 m deep and tens of meters long. There are cracks: closed And open type. Open cracks are clearly visible on the surface of the glacier and therefore pose less of a danger to movement on the glacier. Theory is good, but without a visual image, theory remains just text.

Depending on the time of year, weather and other factors, cracks in the glacier may be covered with snow. In this case, the cracks are not visible and when moving along the glacier there is a danger of falling into the crack along with the snow bridge covering the crack. To ensure safety when moving on a glacier, especially a closed one, it is necessary to travel in bundles.

There is a special type of crack - bergschrund, characteristic of cirques (a cirque, or a natural bowl-shaped depression in the pre-summit part of the slopes), feeding valley glaciers from the firn basin. The Bergschrund is a large crack that occurs when a glacier emerges from a firn basin.

You can read in detail about the types of glacial cracks and their structure in the article.

Now let’s move on to directly viewing visual examples of cracks of various types and sizes:

Glacial crevasse on a "dirty" glacier

Dangerous ice cracks on a “closed” glacier

Rankluft is a crack, a ravine between the glacier and the rocks. Usually rankluft forms at the lateral boundaries of the glacier touching the rocks. Reaches from 1m wide and up to 8 meters deep

TO THE 65TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE GREAT VICTORY

THEY FOUGHT TO THE DEATH FOR THE PASSES OF THE GREATER CAUCASUS

The fascist German troops, having reached the main passes of the Greater Caucasus in the 2nd half of August 1942, resumed active offensive operations, seeking at any cost to capture the oil-bearing regions of Baku and Grozny, as well as to reach the Black Sea to meet their troops in the Tuapse and Novorossiysk directions. The closest pass for connecting with these groups was Marukhsky.

On the path of the selected units of the Edelweiss mountain rifle division, it was not the ridges that became an insurmountable obstacle Caucasus mountains, but the resilience and massive heroism of the soldiers who defended the passes of the Caucasus.

General Rudolf Conrad and his Alpine riflemen from the 49th Mountain Corps were confident of an easy victory.

The Marukh Pass (height 2739 m) in the western part of the Greater Caucasus was covered by the 808th and 810th regiments of the 294th Infantry Division. Alpine riflemen, formed in the mountain villages of Tyrol from the best climbers and skiers, had special mountain equipment and weapons, warm uniforms, and pack transport - mules. They could move quickly in the mountains, climb glaciers and snowy passes.

From August 27 to September 1, there were stubborn battles on the approaches to the Marukh Pass. On September 5, the enemy went on the offensive with the help of the regiment and, having a great superiority in forces and means, captured the pass. But its further advance into Abkhazia and Transcaucasia was stopped by the forces of the 810th regiment, which was stationed in the 2nd echelon.

Immediately beyond the pass was the front line of defense. A line of 1.5-2 km ran from Mount Marukh-Bashi to the northwest and closed the passage to the Marukh Gorge. Our mountain rifle detachments dug in, built dugouts in the rocks, and installed machine guns. 3 more battalions arrived to help the regiment. Throughout September and October, the troops fought for possession of this line with varying success.

On October 25, the 810th regiment occupied height 1176 and the gates of the Marukh Pass, firmly entrenched itself and defended itself among rocks, snow and ice until the end of 1942.

Flying detachments of climbers provided great assistance to our troops. They could be found on mountain paths, on snowy plateaus, and on steep passes. They tracked down the enemy, set up ambushes and blockages on roads and trails, carried out daring raids, and participated in ground and air reconnaissance. They stood against the elite Alpine units of the “Third Reich”, who fought in Norway, Greece, Yugoslavia and gained a lot of experience.

Small groups of rangers managed to penetrate through the Caucasus Range into the area of the Bzyb River. They were seen in the villages of Gvandra and Klidzhe, in the area of Lake Ritsa, 40 km from Sukhum, but they were unable to go further - they were destroyed.

During the same period, the evacuation of civilians was underway. In August 1942, the climbers received an assignment from the command - to bring people living and working at the Tyrnyauz molybdenum plant, located in the Baksan Gorge, through the passes of Transcaucasia, and to remove valuable equipment and raw materials. The escape route along the road was cut off by the Germans. German planes flew over the Baksan Gorge and dropped bombs. Under fire, in difficult weather conditions, a chain of Tyrnyauz residents walked to the pass, led by climbers and their assistants - Komsomol members from the plant. With a lack of climbing equipment and special shoes, climbers led women, old people, disabled people, children and transported valuable equipment on donkeys. Bypassing deep cracks filled with snow, organizing rope crossings, getting into snow charges and thunderstorms, climbers transferred 1,500 adults and 230 children during August.

Anyone who has walked from the Baksan Gorge to Svaneti through the Becho Pass knows that it is accessible only to prepared, trained athletes. I was also convinced of this when I crossed the pass with a group of factory tourists in August 1960. There were also beginners in our group, and if it had not been for the help of climbers passing at the same time, we would have had to experience great difficulties.

After the Soviet troops launched a general offensive in January 1943, the enemy retreated to the north. The enemy's attempt to break through the Marukh Pass to the rear in the Tuapse and Novorossiysk directions and reach the sea failed.

The history of the world’s highest altitude war is presented in the book “The Mystery of the Marukh Glacier” by Vladimir Gneushev and Andrei Poputko, published by the Stavropol Book Publishing House in 1966.

In September 1962, collective farm shepherd Muradin Kochkarov was tending a flock of sheep in the Western Caucasus mountains near the Khalega Pass. Having missed several sheep, Muradin, leaving the flock to his partner, went in search. Came out to small lake- there were no sheep there, he went even higher and soon climbed the ridge. Here he saw several combat cells, human bones, cartridges. Walking along the ridge to the top of Kara-Kaya, I saw traces of fierce battles. On the Marukh glacier he came across the frozen remains of our soldiers. He reported what he saw to the chairman of the village council in the village of Khasaut.

The Stavropol Regional Executive Committee created a commission of military specialists, doctors, and experts and sent it to the Marukh glacier. With them was a platoon of sappers and a group of climbers led by an experienced instructor Khadzhi Magomedov. Coming out along the valley of the Aksaut River to the crest of the ridge, they discovered and collected the remains of the soldiers, and found a field hospital. On highest point of a ridge of 3500 m, in a tour made of stones, there was a note left by tourists who had recently passed by. They wrote that they were shocked by what they saw and suggested calling this nameless ridge “Defensive.”

On the descent from the ridge to the glacier moraine, traces of fierce battles were increasingly encountered. In many places on the glacier there are scattered, half-frozen remains of our soldiers, weapons, and shell casings scattered across the surface of the ice. On the Defense Ridge, a team of sappers destroyed mines and shells.

People carried all the remains of the soldiers across the ridge to a clearing and on horses lowered the mournful cargo into the valley of the Aksaut River, then to the village of Krasny Karachay and from there by car to the village of Zelenchukskaya - the regional center.

People will remember those who were buried in Zelenchukskaya on October 1, 1962 forever. There have never been so many people in Zelenchukskaya - from the very morning they walked here and drove anything, not only from neighboring villages and villages, but also from Karachaevsk, Cherkessk, Stavropol. Neither the stadium, where the military guard and orchestra lined up, nor the park where the remains were buried, could accommodate all those who arrived, and therefore people stood, blocking the neighboring streets.

In the summer of 1959, the Moscow City Tourist School of Sergei Nikolaevich Boldyrev made a transition through the Western Caucasus. 162 participants were divided into 5 groups, 2 of which, having passed north of Kara-Kaya, reached the Northern Marukh Glacier. We had to spend the night on the moraine of the glacier. In the morning, climbing to the Marukh Pass, they began to encounter bones, unexploded grenades, fragments of mines and shells, and shell casings. Even in Moscow, preparing for the campaign, they knew about the traces of fierce battles on the Marukh Pass, but what they saw cannot be expressed in words.

In 1960, a group of students from the Civil Engineering Institute named after. Kuibysheva from Moscow, while making a mountain hike, found the remains of soldiers on the glacier. They buried the nameless soldiers as best they could, and the next year they carried a prefabricated obelisk into the mountains in backpacks and installed it in the glacier area.

Many years later, a massive ascent was made to the Marukh Pass. There they erected a monument and held a rally in memory of our soldiers who fought to the death against the elite units of the Edelweiss division.

In 1961, I led a group of tourists from our plant through the Klukhor Pass, and we found traces of battles. And even in 1974, when I found myself here with factory tourists, I discovered echoes of the battles of 1942.

In 1975, the country was preparing to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Great Victory. I have long been nurturing the idea of organizing a hike to the Marukh Pass area and installing a plaque to its heroic defenders on the rocks of the Defense Ridge from the plant’s tourist club. Alexander Kozlov, chairman of the plant’s tourist club, supported me. Thus, an expedition was organized consisting of mountain and water groups, which were supposed to meet after the hike on May 9 in the village of Zelenchukskaya and take part in a rally and laying a wreath at the monument to the defenders of the Marukh Pass. Alexander Sapozhnikov and Viktor Khorunzhiy were engaged in the production of the board; factory artists prepared two ribbons for the wreath and the board. The trade union committee allocated money for travel and several days of vacation.

Mountain group: Nikolai Lychagin and Mark Shargorodsky - engineers, Tatyana Zueva - technologist, Vladimir Dmitriev - military representative of the plant, Victor Khorunzhiy - electrician and I - Marishina Valentina - designer, leader of the trip.

Water group (3 crews): Valery Gut - standardizer, leader of the trip, Viktor Slabov - technologist, Boris Evtikhov and Alexander Sapozhenkov - engineers, Alexander Ivanov - milling machine operator and Igor Zhashko (not a factory employee), whose father participated in the battles for the Marukh Pass.

The watermen traveled through Cherkessk to Verkhniy Arkhyz, from where they began rafting down the Bolshoi Zelenchuk River.

Our mountain group arrived in Karachaevsk, from there by bus and car to Krasny Karachay and moved along the valley of the Aksaut River to the upper reaches. After a two-day trek in the morning, lightly with ice axes and two backpacks in which the board and fasteners are packed, we begin the ascent to the Khalega Pass. We make a path in knee-deep snow. On the way up to the pass we meet several stone tours, installed boards, and obelisks. At the foot of these monuments there are traces of battles, remains of weapons, rusty iron, cartridges. Leaving the board in a secluded place on the pass, we returned to the tents. The next day, having passed through the Khalega pass along a beaten path, taking a board, we descended into the valley of the Marukha River, filled with snowfields. Not far from the glacier, we stopped for the night in a wooden shelter. The shelter was packed to capacity with tourists - the entire geography of the country. In the morning we climbed the Defense Ridge, found a ledge with a flat platform for the board, where the next day we installed and secured the board, using ropes for belaying and lifting the board with the text: “To the heroic defenders of the ice fortress of the Marukh Pass, who stood to the death to the end, not letting it through Transcaucasia in August - December 1942. From the factory youth and the factory tourist club. Moscow city. May 1975." Pine branches with ribbon and lilacs from the village of Krasny Karachay were secured under the board.

We met the senior pioneer leader of the school, and she offered to make a wreath from the group at their school. We made a gorgeous wreath of spruce branches, added fresh flowers to it, attached a ribbon, and took it out of school on May 9th. Pioneers and schoolchildren also brought out their wreath. A rally took place at the stadium. I have never seen Victory Day celebrated like this anywhere. The stadium was full to capacity. Everyone with wreaths, flowers, baskets, flags - veterans, youth, pioneers, children, mothers with strollers.

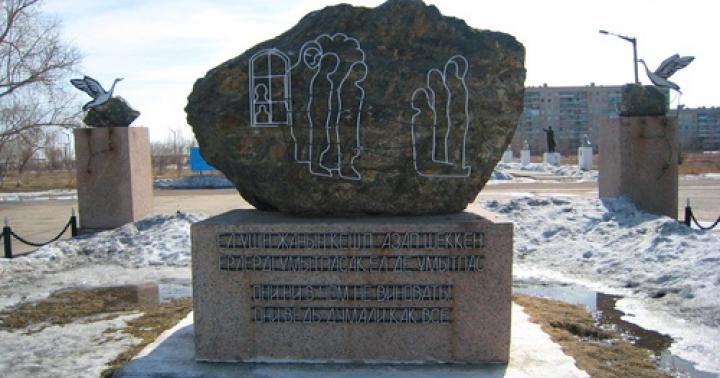

Photo

After the meeting, everyone moved in organized columns to the park to the monument to the defenders of the Marukh Pass, where the eternal flame burns. There are many tourists in the columns who have come down from the mountains. Young children, school students, stand on the guard of honor.

Photo

Wreaths, baskets and flowers were laid at the monument. On the dark stele of the monument there is a light board with the image of a machine gun and an ice ax.

We presented the pioneer leader, who helped us with making the wreath, with a figurine of a warrior - the defender of the Marukh Pass, made by our factory craftsman, for the school museum.

On the bank of Zelenchuk, after all the celebrations, the groups gathered at the festive table. They came to us local residents, sat with us by the fire, singing war songs. The people are very friendly, there are many children.

Having passed many passes in the Caucasus, I saw dozens of obelisks, memorial plaques, pyramids with stars, raised on their shoulders by tourists from many cities of our Soviet country. At the Becho Pass, tourists from the Odessa tourist club “Romantic” installed a large silver plaque on the rock, on which are written the names of 6 climbers who accomplished the feat of leading the inhabitants of the Baksan Gorge through the pass to Svaneti. On the board there is a warrior in a helmet with a star and a little girl with her arms wrapped around his neck.

The geography of cities whose tourists lifted these modest monuments into the mountains on their shoulders is great: Odessa, Donetsk, Moscow, Kharkov, Dnepropetrovsk, Leningrad, Rostov, Krasnodar, Stavropol... I remember one obelisk with a star and a massive plaque with the inscription “To the Defenders North Caucasus", installed by Komsomol members of the city of Chapaevsk, Kuibyshev region (now Samara).

The passes of the Caucasus were defended by soldiers of many nationalities of our Great Country - the USSR. In addition to the soldiers, the Marukh Pass was defended by sailors of the Black Sea Fleet. The memory of grateful descendants for the great feat of our fathers and grandfathers must be passed on to the generations following us.

Valentina Marishina,

Moscow

Warning function.include on line 123

Warning: include(../includes/all_art.php) [function.include ]: failed to open stream: No such file or directory in /pub/home/rada65/tourist/www/articles/pobeda.php on line 123

Warning: include() [function.include ]: Failed opening "../includes/all_art.php" for inclusion (include_path=".:/usr/local/php5.2/share/pear") in /pub/home/rada65/tourist/www/articles/pobeda.php on line 123

Zones of crack formation can be predicted by knowing the nature of the glacier and the surface on which it is located. Fracture zones usually form in places where the ice flow changes direction - on turns, depressions and bends. Ice and cracks are often covered with a layer of snow. There is a danger of falling into a crack. On closed glaciers they move in teams, with careful insurance, constantly probing the path in front of them.

The first team when reconnaissance of the route route should consist of three people. The fall of one into a crack should not lead to the other two being pulled into it. The rope must be fully extended (do not leave rings, do not allow slack in the rope). The movement of participants within the ligament and between the ligaments is one after another.

When a group moves from ice to rocks you may encounter coastal crack (Rantkluft), running along the body of the glacier and formed due to the temperature difference - the stones heat up more than the ice, and the latter melts near the rocks. Such cracks (Fig. 1) have a relatively small depth. To pass them, you can almost always find an area where they are covered with fragments of rocks or ice.

When the slope of the glacier bed changes, transverse cracks appear in its body.

With a significant increase in the steepness of the bend, due to the fragility of the upper layers and the greater (compared to the lower layers) speed of their movement, significant cracking of the glacier surface occurs, and the fall of the separated masses of ice occurs. Such zones of intense ice destruction called icefalls.

Where the glacier, following the shape of the valley, makes turns, formations form in its body. radial cracks, fan-shaped and expanding towards outside bending Here path groups must pass near the shore along the slope closest to the center of the turn.

When a glacier emerges from a gorge onto a wider section of the valley, longitudinal cracks. In the case of a closed glacier these are the most dangerous cracks. Here, all tourists in one group can, without suspecting danger, walk along a crack in the immediate vicinity of it, and the fall of one of the tourists into the crack will inevitably cause the rest to fall. In such cases, it is advisable to move either along the convex shapes of the glacier or along a serpentine line with a line angle of 45 degrees relative to the longitudinal axis of the glacier.

When moving along the convex forms of the glacier's relief, tourists may encounter mesh (crossing) cracks, which occur when ice creeps onto a protruding part of solid rock at the bottom of a valley. As a result, the ice swells and longitudinal and transverse cracks are formed, intersecting each other (Fig. 2). It is better to avoid these cracks. If, when going around such a zone, there is a danger of encountering longitudinal cracks existing in it, then it is best to bypass the latter along the lower boundary of the convex shape. Here tourists can only expect transverse cracks.

Snow cornices may form at the edges of cracks. Therefore, if it is necessary to move near large open cracks, it is necessary to first inspect (with careful insurance) the nature of the crack and the cornice.

In the upper reaches of glaciers, parallel to the slopes of the cirque, arched foothill cracks (bergschrund), having a large width and depth in their central part (Fig. 3). Closer to the base of the arch, in its lower part, the width of the crack decreases, disappearing. If a bergschrund is a series of arches, then most often their bases are not connected, but are located one above the other, forming possible passages. In summer, you can also look for a passage through the bergschrund in the concave part of the slope, which in the spring is a chute for avalanches. Avalanches form strong bridges here. Of course, this path should be chosen only when avalanches have already occurred (in no case after a snowfall). The approach to the snow bridge must be made from a safe area one at a time, with an observer posted. Those who have passed the dangerous section immediately leave the danger zone. Such bridges and the entire danger zone should be crossed in the morning with careful insurance.

Before the crack transitions over the snow bridge You must first examine it carefully. If a group moves across the bridge, tourists cross it on their bellies, with insurance, but without backpacks. At the same time, they should try to distribute their body weight over as large a surface as possible. Even across bridges that are not entirely reliable, you can transport the entire group in this way. Backpacks are dragged separately.

Cracks on closed glaciers- serious danger. Falling in them without reliable and correct insurance usually leads to injury. If the fallen person is not injured, but is unable to move (jammed, unreliable support on which the fallen person managed to stay, etc.), lack of rope or the inability of other participants in the trip to organize the lifting of the tourist from the crack in a timely manner, leads to his rapid freezing.